|

AN INTERVIEW WITH GERT SCHEERLINCK, AFTER 4 YEARS OBSERVING HIS USE OF NEGATIVE SPACES

CARMEN HUST | FEBRUARY 2019 Back in 2015, we had the pleasure of interviewing Belgium artist Gert Scheerlinck in his venture of an object oriented approach to his artistic practice, where he chose to expose other peoples trash, in the consideration that the objects are still useful (as other people’s treasure). Read GERT SCHEERLINCK COMBINES AND RELOCATES EXTENSIVELY USED OBJECTS (2015) here

Today the approach of Gert Scheerlinck differs from that of four years ago. We've met him and had a conversation in the aim to grasp his flow.

We've been following you for quite some years now. We’ve noticed a certain transition from object-oriented work to a more conceptual thinking. We wonder: to what do we owe this change? A few years ago, I mainly focused on the found object, everything started with the object. By experimenting, a rather intuitive and minimalist work would arise. With time, I felt that, something was missing in the process. It had nothing to do with what I wanted to tell, but how. I realized that the found object forced its will upon me and I had to distance myself from it. In order to penetrate my own work, I had to question it. This new way of thinking that influenced your work in the studio, how did that manifest itself?

I spend less time experimenting in my studio. I made myself less dependent of the object and that somehow freed me. This resulted in a different perspective allowing me to work with other media as well (like video, neon and even potatoes, …). However, the minimalistic approach and the materials remain an important part of my work. Relative to the “evil” world, I want to continue to cherish the small and personal. [silence] I do not try to be crushed by the enormous forces that come to us in Western society: efficiency, dominance of economic business models, alienation, loss of tolerance and caring for each other. It is not insignificant what we are experiencing in the West. Going back to a micro level of thinking and acting certainly offers some solace, because as a person you can hardly influence those great powers. |

It seems you’re also working with emptiness, or negative spaces, as a conceptual tool. Seeing your work How to draw a Line, the line is defined by the edges of the pencils, but the line itself is empty and not drawn (or undrawn) with lead. How is it to fathom the empty spaces, in terms of those being your actual work?

Emptiness and negative spaces indeed are like the clever use of silence in movies, to create heightened awareness in key scenes. The absence of non-diegetic composition can add an extra level of “emotion”. It's the moment you start to reflect and where imagination takes over. John Cage would say: “There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear.” I believe that my work has many layers and one can interpret it in various ways to help you understand life and maybe even create a self-identity. Talking about identity and empty spaces, one easily has the tendency to place your work within the concept of heterotopies thoroughly explained by Foucault. Your work has a refined tendency to simulate the ordinary, but framed by its contrast, which makes it utterly remarkable. How did you discover the way to resemble the complex by making it simple?

Good point. Heterotopias are worlds within worlds, mirroring and yet upsetting what is outside. It’s all about the imaginary space that is created, it questions human interactions, moments of solitude and feelings. In relation to minimalism, I return to the essence and ask crucial questions. A derived truth arises by throwing all the superfluous overboard. “Make it simple” as you describe it. How this works exactly is hard to say, you can look at the individual action of the artist, but rather it is a flow of thoughts that stray to come to the final work. It’s the unique self of the artist that you simply cannot explain. Asking crucial questions, as an opponent to face whatever is presented uncritically, could also lead one to think of other Foucaultian proposals. Deconstruction could perhaps help us one step further. Do you somehow feel that the post-human epoch (and its human inhabitants) is in need of discovering new relations, or combined networks, to the objects and subjects surrounding them? And is this somehow what your work is facilitating? |

No, no, no, you go into it way too deep. Let’s not make it too complicated by linking too many philosophical ideas to it. My vision mainly refers to minimalism, it assists me to get rid of life’s excess in favor of focusing on what brings value to life. I would have rather answered: "my work is what it is" and leave it at that, but then people ask me profound questions and I find myself responding with far-fetching descriptions. It’s a trap. [Laughs]

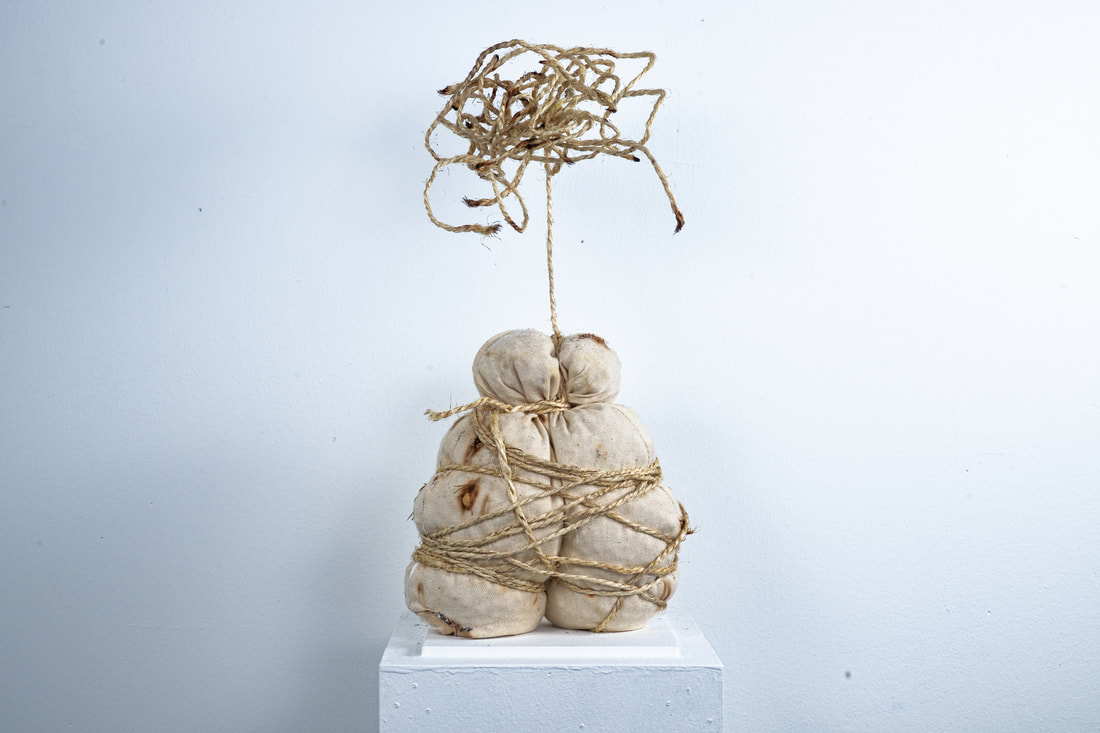

[Laughing] you are not alone in that thought. But on the other hand (looking at How to draw a line or Chuño), you do have some comment upon the current global and political situation – how does that balance with the statement “my work is what it is”? I know it might be confusing. On the one hand, I make poetic work that articulates into smaller work that contains color and feels warm. 'My work is what it is' fits perfectly, because how can you explain poetry? Poetry is something you must interpret on a personal level. On the other hand, I also make work that’s critical to society. There is a certain, often dark, message that can’t always be read clearly. I agree that the line between poetical and critical is very thin. That makes it so fascinating.

Chuño is such a work where you can go both ways, it has its poetic approach, but also its critical one. The title Chuño refers to the ancient tradition of freezing potatoes. Villagers living in Bolivia & Peru make Chuño by using the warm days and freezing nights. Crushing them underfoot they remove the skin and push out the liquids. Once dried, the product can last for a very long time, sometimes decades. But because of climate change, temperatures are not dropping as low as they where before and the tradition is doomed to disappear. The work Chuño is an attempt to reach the viewer, but not in a compelling activist way but through a poetic approach. This interview with GERT SCHEERLINCK is a follow-up on the interview from 2015, part of ARTICULATE #3. Read, download or order your print version of the full publication (#3) below.

|

SUPPORTARTICULATE

www.articulate.nu SUPPORT Monday - Friday 8:00 - 16:00 [email protected] +45 30 48 19 81 Head Quarters VAT DK40953191 |

|