𝐕𝐮𝐥𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐬, 𝐩𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐩𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞-𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐬. 𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧: 𝐏𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐀𝐫𝐭 𝟏.𝟎Pandemic Art 1.0

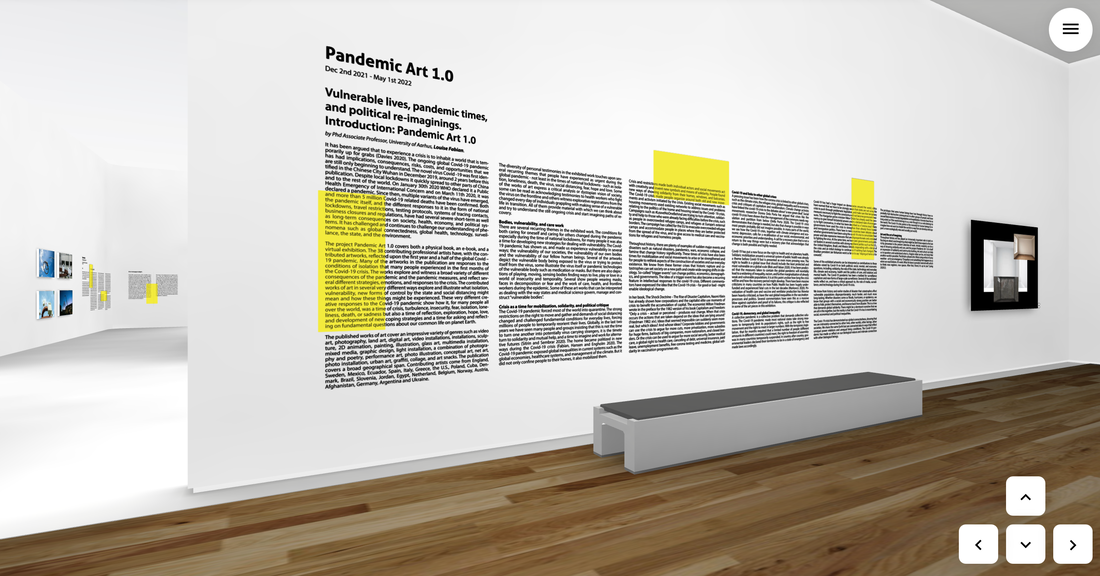

A project by ARTICULATE Introduction by Louise Fabian Online Exhibition December 2nd 2021 - May 1st 2022 Book Release December 3rd 2021 E-book Release December 9th 2021 |

𝐕𝐮𝐥𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐬, 𝐩𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐩𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞-𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐬.

𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧: 𝐏𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐀𝐫𝐭 𝟏.𝟎 an article written by Phd Associate Professor, University of Aarhus, Louise Fabian

It has been argued that to experience a crisis is to inhabit a world that is temporarily up for grabs (Davies 2020). The ongoing global Covid-19 pandemic has had implications, consequences, risks, costs, and opportunities that we are still only beginning to understand. The novel virus Covid -19 was first identified in the Chinese City Wuhan in December 2019, around 2 years before this publication. Despite local lockdowns it quickly spread to other parts of China and to the rest of the world. On January 30th 2020 WHO declared it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and on March 11th 2020, it was declared a pandemic. Since then, multiple variants of the virus have emerged, and more than 5 million Covid-19 related deaths have been confirmed. Both the pandemic itself, and the different responses to it in the form of national lockdowns, travel restrictions, testing protocols, systems of tracing contacts, business closures and regulations, have had several severe short-term as well as long-term consequences on society, health, economy, and political systems. It has challenged and continues to challenge our understanding of phenomena such as global connectedness, global health, technology, surveillance, the state, and the environment. The project Pandemic Art 1.0 covers both a physical book, an e-book, and a virtual exhibition. The 38 contributing professional artists have, with the contributed artworks, reflected upon the first year and a half of the global Covid – 19 pandemic. Many of the artworks in the publication are responses to the conditions of isolation that many people experienced in the first months of the Covid-19 crisis. The works explore and witness a broad variety of different consequences of the pandemic and the pandemic measures, and reflect several different strategies, emotions, and responses to the crisis. The contributed works of art in several very different ways explore and illustrate what isolation, vulnerability, new forms of control by the state and social distancing might mean and how these things might be experienced. These very different creative responses to the Covid-19 pandemic show how it, for many people all over the world, was a time of crisis, turbulence, insecurity, fear, isolation, loneliness, death, or sadness but also a time of reflection, exploration, hope, love, and development of new coping strategies and a time for asking and reflecting on fundamental questions about our common life on planet Earth. The published works of art cover an impressive variety of genres such as video art, photography, land art, digital art, video installations, installations, sculpture, 2D animation, painting, illustration, glass art, multimedia installation, mixed media, graphic design, light installation, a combination of photography and poetry, performance art, photo illustration, conceptual art, net art, photo installation, urban art, graffiti, collage, and art snacks.

The publication covers a broad geographical span. Contributing artists come from England, Sweden, Mexico, Ecuador, Spain, Italy, Greece, the U.S., Poland, Cuba, Denmark, Brazil, Slovenia, Jordan, Egypt, Netherland, Belgium, Norway, Austria, Afghanistan, Germany, Argentina and Ukraine. The diversity of personal testimonies in the exhibited work touches upon several recurring themes that people have experienced as urgent during the global pandemic - not least in the times of national lockdowns - such as isolation, loneliness, death, the virus, social distancing, fear, hope and love. Some of the works of art express a critical analysis or dystopian vision of society, some can be read as acknowledging testimonies to health workers who fight the virus on the frontline and others witness explorative registrations from the changed every day of individuals grappling with making sense of a vulnerable life in transition. All of them provide material with which we can think about and try to understand the still ongoing crisis and start imagining paths of recovery. 𝐁𝐨𝐝𝐢𝐞𝐬, 𝐯𝐮𝐥𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐲, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐤

There are several recurring themes in the exhibited work. The conditions for both caring for oneself and caring for others changed during the pandemic especially during the time of national lockdowns, for many people it was also a time for developing new strategies for dealing with vulnerability. The Covid- 19 pandemic has shown us, and made us experience vulnerability in several ways; the vulnerability of our societies, the vulnerability of our own bodies and the vulnerability of our fellow human beings. Several of the artworks depict the vulnerable body being exposed to the virus or trying to protect itself from the virus, some illustrate the virus itself or pandemic technologies of the vulnerable body such as medication or masks. But there are also depictions of playing, moving, sensing bodies finding ways to live, play or love in a world of insecurity and temporality. Several show people wearing masks, faces in decomposition or fear and the work of care, health, and frontline workers during the epidemic. Some of these art works that can be interpreted as dealing with the way states and medical science govern, manage and construct “vulnerable bodies”. 𝐂𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐬 𝐚 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐦𝐨𝐛𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐳𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐬𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐝𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐭𝐲, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐩𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐪𝐮𝐞 The Covid-19 pandemic forced most of the world into quarantine. The strong restrictions on the right to move and gather and demands of social distancing changed and challenged fundamental conditions for everyday lives, forcing millions of people to temporarily reorient their lives. Globally, in the last two years we have seen many people and groups insisting that this is not the time to turn one another into potentially virus carrying strangers, it is the time to turn to solidarity and mutual help, and a time to imagine and work for alternative futures (Sitrin and Sembrar 2020). The home became politized in new ways during the Covid-19 crisis (Fabian, Hansen and Engholm 2020). The Covid-19 pandemic exposed global inequalities in current systems such as the global economies, healthcare systems, and management of the climate. But it did not only confine people to their homes, it also mobilized them. Crisis and restrictions made both individual actors and social movements act with creativity and invent new symbols and means of solidarity. People found new ways of showing solidarity from their homes, windows, and balconies. The Covid-19 crisis made people organize around both old and new movements and activism initiated by the crisis. Existing social movements such as housing movements used existing networks to address issues and problems relating to the politics of the home and housing raised by the Covid- 19 crisis. Campaigns such as #LeaveNoOneBehind are trying to turn attention, solidarity and help to those who were already facing difficulties before the crisis, such as people in overcrowded refugee camps, and refugees at Europe’s external borders. The campaign has called for the EU to evacuate overcrowded refugee camps and accommodate people in places where they are better protected from the spread of the virus, and to give access to medical care and vaccinations for refugees and homeless people. Throughout history, there are plenty of examples of sudden major events and disasters such as natural disasters, pandemics, wars, economic collapse, and famine that change history significantly. These times of crisis have also been times for mobilization and social movements to arise or be strengthened and for people to rethink aspects of the construction of societies and our everyday existence. We know from these former crises that historic rupture and catastrophes can set society on a new path and create wide ranging shifts in ideology. So-called “trigger events” can change politics, economics, demographics, and governments. The idea of a trigger event has also become a recurring feature in intellectual responses to the covid-19 crisis. Different commentators have expressed the idea that the Covid-19 crisis – for good or bad - might enable ideological change.

In her book, The Shock Doctrine – The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, Naomi Klein has already shown how corporations and the capitalist elite use moments of crisis to benefit the accumulation of capital. The economist Milton Friedman wrote in the preface for the 1982 version of his book Capitalism and Freedom: “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.” (Friedman 1982: xiv). Ideas that seemed impossible can suddenly seem more real, but which ideas? And whose ideas? Corporate lobbies and governments can use the crisis to argue for more cuts, more privatization, more subsidies for huge firms, bailouts of big companies, more nationalism, and closed borders. Or the crisis can be used to argue for more social security, better medical care, a global right to health care, canceling of debt, universal insurance, paid leave, unemployment benefits, free corona testing and medicine, global solidarity in vaccination programmes etc. 𝐂𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝-𝟏𝟗 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐤𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐠𝐥𝐨𝐛𝐚𝐥 𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐬

A pressing issue has been how the corona crisis is linked to other global crises, such as the climate crisis, the refugee crisis, global inequality and to economic crisis and critiques of capitalism and neoliberalism. Climate change activists have linked the covid-19 crisis to the debates about “a new green deal”. Social movements researcher Donna Dela Porta has argued that crises like the covid-19 crisis have shown that the management of the commons needs regulation and partition from below (Della Porta 2020). The Covid-19 crisis demonstrates that change is needed, but also that change is possible in ways most people probably did not imagine possible. In many parts of the world, we see how the Covid-19 crisis, together with climate emergence and economic depression, calls for a recalibration of our social, environmental, and economic priorities and understanding. A call for a recovery plan that is not a return to the way things were but a recovery plan that acknowledges that change is both possible and highly needed. Covid-19 has put a new focus on the right to health and on planetary health. Solidaric mobilization around a universal system of public health was already a theme before Covid-19 but is presented as even more pressing now. The right to health is a global issue that should include the least protected and most vulnerable on a global scale (Blok and Fabian 2020). It has been predicted that the measures taken to contain the global pandemic will inevitably lead to a widening of inequality, racism, and further marginalization of already weak and vulnerable populations. It is at this point unclear how long the crisis will be and how the recovery period might develop. There have been massive criticisms in many countries on how Public Health has been hugely underfunded and experienced fatal cuts in the last decades (Markovcic 2020). Privatization of health care and vaccine and ventilator production has likewise been heavily criticized, as have the vast global inequalities in the vaccination processes and politics. Several commentators have seen this as a massive blow against capitalism and proof of its failures, this critique is also reflected in some of the art pieces in this exhibition. 𝐂𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝-𝟏𝟗, 𝐝𝐞𝐦𝐨𝐜𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐲, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐠𝐥𝐨𝐛𝐚𝐥 𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐪𝐮𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐲 A collective pandemic is a collective problem that demands collective solutions. The Covid- 19 pandemic made most national states take strong measures to temporarily limit its population’s rights, such as the right to free movement and the right to meet in larger numbers. With the temporary legislation, that for months required that a limited number of people (different amounts in different countries) could meet, the right to freedom of assembly was in many countries temporarily suspended. In country after country, governmental leaders declared their territories to be in a state of emergency and made laws accordingly. Covid-19 has had a huge impact on democracies around the world, critics have warned that we have to be strongly aware that states are not using the crisis to push through problematic legislation, and make sure that temporary measures necessary to fight the coronavirus will not become permanent measures. The Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán has already used the coronavirus to give himself dictatorial powers under a declared state of emergency to fight coronavirus, in what has been described as a “corona coup”. Many governments have used the crisis to strengthen their already fierce border and immigration politics. There have in many countries been debates about whether governments have been using the covid-19 crisis to consolidate their power and take repressive measures that are disproportionate and unrelated to fighting the virus. At the same time, we have seen governments and political leaders in several countries with strong neoliberal politics such as the U.S., the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Mexico initially responding with a denial of the crisis and an initial strategy to continue as if nothing had changed. The Brazilian president Jair Bolsanaro went so far as to say: “staying at home is for cowards”. Some of the exhibited artworks can be interpreted as contributions to these debates raised by Covid-19 on both political, social, mental, and economic questions, including; solidarity, the role of the state, technology and everyday life, climate and economy, health and the politics of care, and isolation and mental health. The Covid-19 pandemic has been a testbed for surveillance capitalism and new forms of large-scale surveillance. Several of the exhibited works reflect on, and have a critical approach to, the role of media, surveillance, and technology during the Covid-19 crisis.

We know from history and earlier studies of disaster that catastrophes affect vulnerable populations disproportionately, much harder, and much more long-lasting. Whether disasters come as floods, hurricanes, or epidemics, we know that groups with a social and economically strong position are better able to hide, protect themselves, and bounce back from disaster. This is a time that demands global solidarity. There might be a dominant narrative that we are all in this together, but the reality is that the Covid-19 virus is exacerbating social, economical and political inequalities. The Covis-19 crisis has demonstrated our global connectedness, showing that we are intimately connected to other lives, other worlds, other beings, other societies. We share the same Earth but are connected also in ways that reflect unequal power relations and unequal living conditions. The Covid-19 pandemic has made us reflect on our biological nature and intimate connection with other biological beings. The privileges that some human beings have had through history have repeatedly had destructive consequences to other groups of people and have caused fatal environmental degradation and exploitation. Humans have for so long acted as if the world belongs to us, even though it is us who belongs to the world. The Covid-19 crisis points to the necessity for human beings to reimagine how we want to inhabit the world in a way that can develop and support a more ecologically wise and socially just world. 𝐀𝐫𝐭 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 Throughout history art has played an immensely important role in both reflecting on what is and imagining what might be. Both these aspects of art are richly presented in the present selection of work. Artistic creativity can be a way of showing solidarity and care, and the project Pandemic Art 1.0 is itself an expression of solidarity and community building. Art and culture can help us to question and understand what is, imagine what can be, and insist that another world is possible. The British cultural critic Olivia Laing writes in Funny weather – art in an emergency: “Empathy is not something that happens to us when we read Dickens. It’s work. What Art does is provide material with which to think: new registers, new spaces. After that, friend, it’s up to you” (Laing 2020:2). 𝐁𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐨𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐩𝐡𝐲

Cohen, Ed (2011).‘The Paradoxical Politics of Viral Containment; or, How Scale Undoes Us One and All’ in Social Text 106 • Vol. 29, No. 1 • Spring 2011, Duke University Press Davies, William (2020): ‘The last global crisis didn’t change the world. But his one could’ in The Guardian 24 March 2020 Della Porta, Donna (2020): Social movements in times of pandemic .https://www.opendemocracy.net/.../social-movements-times.../ Fabian, Louise and Blok, Gemma (2020): ‘Introduction: Vulnerable Bodies and ‘the Public' in Public Health’ in Marginalization and Space in Times of COVID-19: The Narcotic City Lockdown Report. Essen : Narcotic city, 2020. p. 3-11. Louise Fabian, Anders Lund Hansen and Mads Engholm (2020) Care and homelessness in the shadow of planetary crisis in Marginalization and Space in Times of COVID-19: The Narcotic City Lockdown Report. Essen : Narcotic city, 2020. p. 19 - 33 Friedman, Milton (1982). Capitalism and Freedom: Fortieth Anniversary Edition, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London Naomi Klein (2008) The Shock Doctrine – The Rise of Disaster Capitalism Penguin Books Markovcic, Andrej (2020) ’Capitalism caused the Covid-19 crisis’ in Jacobin 04 April 2020 orki://jacobinmag.com/2020/04/coronavirus-covid-19-crisis-capitalism-disaster Sitrin, Marina and Sembrar, Colectiva (2020) Pandemic Solidarity – Mutual Aid during the Covd-19 Crisis Pluto Press, London |

SUPPORTARTICULATE

www.articulate.nu SUPPORT Monday - Friday 8:00 - 16:00 [email protected] +45 30 48 19 81 Head Quarters VAT DK40953191 |

|