Digital Street Art in an Augmented Reality: AR combines physical and virtual elements and is a promising playground for contemporary digital art, displayed at DEMO-. |

an article written by Joachim Aagaard Friis

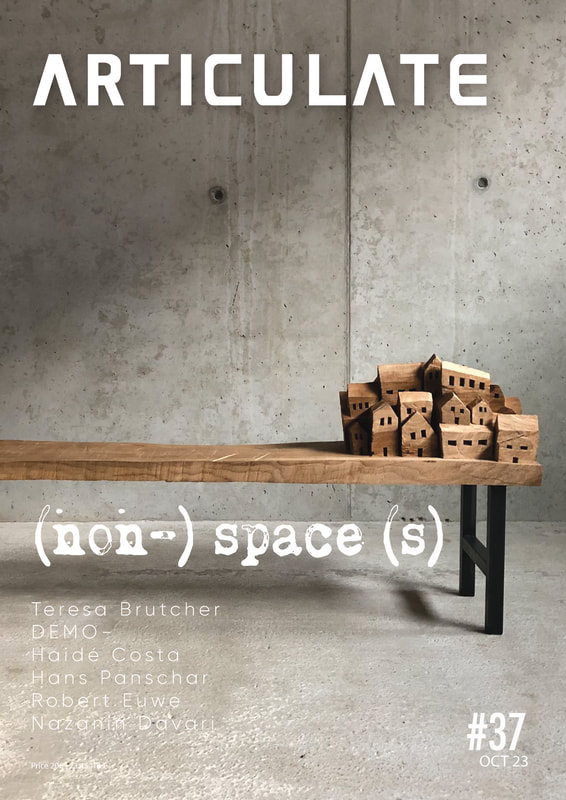

The virtual city. Augmented Reality combines physical and virtual elements and is a promising playground for contemporary digital art. But can site-specific art be created through a screen? The AR exhibition DEMO- in Frankfurt attempts to explore how the medium can be used in public spaces. In front of Paulskirche square in Frankfurt, a large white bird lands, resembling a mix between an eagle and a dove. It delicately hovers a little above the ground, occasionally tilting its head. As the bird towers in front of me, it appears real enough. But people seeing me walking around and peering into a large iPad might wonder why I'm circling an empty area in the square. The answer is AR, which stands for Augmented Reality. Unlike VR (virtual reality), which creates a completely animated world for the viewer, AR refers to a variation of a real environment created through computer-generated information with visual and sonic stimuli. The technology inserts digital objects using the camera function on one's phone. Some have already encountered AR in popular games like the 2017 craze Pokémon Go. However, the utility of AR goes beyond just games. In recent years, it has become a new medium in contemporary art. Artists experiment with the medium's blend of digital and "real" layers, using it as a way to visualize underrepresented narratives and criticize political censorship. As our own reality becomes increasingly screen-based, AR art can serve as a way to engage with and perhaps even shape the reality that is becoming more digitized. Site-specific and digital?

The potential of AR technology to influence public spaces is the foundation of the DEMO- exhibition in Frankfurt, where Flaka Haliti's aforementioned white bird (Whose Bones?, 2022) is featured. Its oversized blend of eagle and dove is meant to symbolize a blurring of the boundary between the powerful and the powerless by merging the symbol of German self-awareness with the most common city bird. Ben Livne-Weitzman, curator of DEMO-, explains this while we stand with iPads in hand, surrounded by physically invisible works at Paulsplatz. I ask him to elaborate on the relationship between AR art and public spaces: "Streets and squares have always been important places for creativity and politics, from demonstrations to posters, graffiti, and street art. Today, every physical space is simultaneously an extended digital space, and thus AR allows for visual interventions and interactive installations. With this exhibition, we aim to explore how to critically engage with public space in a digitized era." The occasion for the exhibition is the 175th anniversary of the Paulskirche assembly. It was the first constituent national assembly and the starting point for democratic governance in Germany, held right in front of Paulskirche in Frankfurt. Digital art pioneer Tamiko Thiel directly addresses this historical context in her work for the exhibition. As a precursor to the use of AR in contemporary art, she is one of the founding members of Manifest.AR, an artist group that in the early 2010s staged activist AR works at major art institutions like Tate Modern, the Venice Biennale, and the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York. In DEMO-, she participates with the work "Revolution and Return" (2023). First, silver coins with portraits of German princes rain down from the sky onto Paulsplatz, surrounding the viewer. If one taps on the coins, they transform into the constitutional documents from the assembly in Paulskirche in 1848. Johann Strauss Jr.'s "Revolution March" plays in the background, and over time, the music becomes more and more discordant. Gold coins with portraits of the Prussian king and Austrian emperor start falling from the sky instead of silver coins. Gradually, the gold coins bury the documents of the revolution, leaving only the clinking sounds. The online materials of the exhibition state that the revolutionary movement was already under attack from reactionary forces in March 1848. In July 1849, Prussian and Austrian troops used military power to crush the first attempt to create a democratically constituted national state. The work testifies to the consequences for the establishment of Germany's first parliament, which, ironically in the context of the 175th-anniversary celebration, initially failed. I'm still somewhat skeptical about AR technology's potential to revolutionize contemporary art, as I stand there manipulating coins into documents on the screen with my finger. And even Strauss drowns in the city's noise when the music plays from small iPad speakers. The interactive element makes Thiel's work resemble a game, and one really needs to delve into the background of the work to fully understand its historical references. It's interesting that the work brings out the challenges of the nascent democracy in the spotlight on the very square where it was established. But it still feels somewhat comical to stand and gaze into a screen to see site-specific art. Aren't we already looking at screens enough in our daily lives? Livne-Weitzman doesn't agree with that conclusion. He explains that the initial idea for the exhibition came from projection-based actions in demonstrations in Israel, which he participated in back in 2015. Digital projections were used as a form of taking over public space, something that couldn't be criminalized like graffiti, for example. It became a tool for political agency that couldn't be punished because the digital projections left no trace. He wanted to recreate this use of existing digital tools for political purposes in Frankfurt, where he has lived for several years now. Invisible Critique

The title DEMO- is a prefix for both democracy and demonstration. It also simply stands for demo, in the sense of a first attempt. The exhibition is indeed one of the first consisting solely of AR works and can only be accessed through an app. There's nothing in the physical surroundings indicating that artworks exist right there on Paulsplatz. No sign or QR code, which one might have expected. Instead, all the works are tied to the app, and they're accessed based on the GPS coordinates set for the works. This way, one can only see the works at very specific designated locations. "The reason we chose this solution is that otherwise, we wouldn't have been granted permission to use these public places. By using the app, we were independent of the restrictions that public space otherwise entails," Livne-Weitzman says. The app, called WAVA, enables artists to place site-specific digital works anywhere without requiring permission. Thus, it can also serve as an alternative to large corporations, which Livne-Weitzman believes will dominate the AR sphere in the future. Just like social media today is an arena for companies, AR will become a profitable digital tool. "We're already heading in that direction. We see it with our phone screens losing their 'frame' and becoming one big image that can be used to see the world through. The goal of a platform like WAVA is to help create alternative infrastructures in this new semi-digital landscape, which will inevitably become a part of our everyday life," he says. I ask whether the app doesn't limit the accessibility of the exhibition despite its advantages. One can only find information about both the exhibition and the app on the internet, which could create some echo chambers. Livne-Weitzman acknowledges that it might exclude some from the exhibition when there are no physical signs of its existence. "But on the other hand, we have much more freedom in terms of where we want to place the works, and the artists have the opportunity to critically engage with public squares, buildings, and monuments." An example of the latter is the artwork "Bunte Stoffe – Eine Hymne" (2023) by the artist duo Les Trucs inside Paulskirche. Inside the church, coats of arms for each state in Germany are hung, symbolizing the united and democratic realm. When one walks along the church wall and focuses on the different coats of arms with their phone, each flag will start emitting sounds as if they're "warming up their vocal cords." When all flags are scanned, a choir sings from the speakers. Playfully, the duo has reinterpreted regional German hymns, changing their vocabulary and randomly rearranging the words that characterize the hymns. Here, AR technology works much better than in Thiel's work, as Les Trucs' hymn requires more engagement with the physical space. One can't help but notice the individual symbols that have characterized the flags' national identity, because one needs to scan each flag in the church before the sound piece begins. That reflection accompanies the sound piece well. Virtual Symbolic Value

Critique of authority is also a theme in Ahmet Öğüt's series "Monuments of the Disclosed" (2022). The series includes nine busts of lesser-known heroes whom Öğüt wishes to honor, five of which are presented in this exhibition. One of the works portrays Dr. Li Wenliang, who warned about Covid-19 in December 2019 and was subsequently accused of spreading false rumors by the police in Wuhan. By placing the bust in front of the Chinese embassy, the work cleverly utilizes AR technology. Wenliang's monument had never been allowed to be erected in this place, but with AR, such censorship can be circumvented (at least for now). Phillip Saviano's bust is equally provocatively placed in front of Frankfurt's cathedral. Saviano's story of having been abused by a Catholic priest, which he came forward with as early as 1992, was crucial in exposing the systemic abuse of children by Catholic priests. Once again, it's an artistic critique made possible through AR's blending of digital and physical reality. At the same time, the works touch upon the debate about monuments in public space that has been prevalent in many Western countries in recent years. Despite the many political messages and expressive animations in DEMO-, I still have doubts about AR's artistic prospects. It could be a passing fad, much like NFTs, which were the big news in digital art a few years ago; in a short time, they've lost their novelty, and their average price has dropped drastically. At the same time, it feels as if the idea of the critical potential of AR art has more impact than the actual experience of standing with a screen in front of you, watching animated figures. In other words, the symbolism of having a statue of Phillip Saviano in front of a cathedral is greater than the aesthetic experience AR provides when you witness the work. However, that's also the case with many other types of conceptual art, so it shouldn't be the death knell for AR. The purely aesthetic shortcomings of AR technology in the exhibition are partly offset by the fact that the works can be experienced and exhibited publicly, freely accessible and without permission, and you can share this experience with others from your own phone. It's the activist and social dimension that makes AR interesting and counters the typical criticism that new digital inventions necessarily lead to fewer physical encounters and isolate users. With all these potentials, AR could indeed be a way to radically change the way we experience art in public space. |

SUPPORTARTICULATE

www.articulate.nu SUPPORT Monday - Friday 8:00 - 16:00 [email protected] +45 30 48 19 81 Head Quarters VAT DK40953191 |

|